Political Stances: Introduction

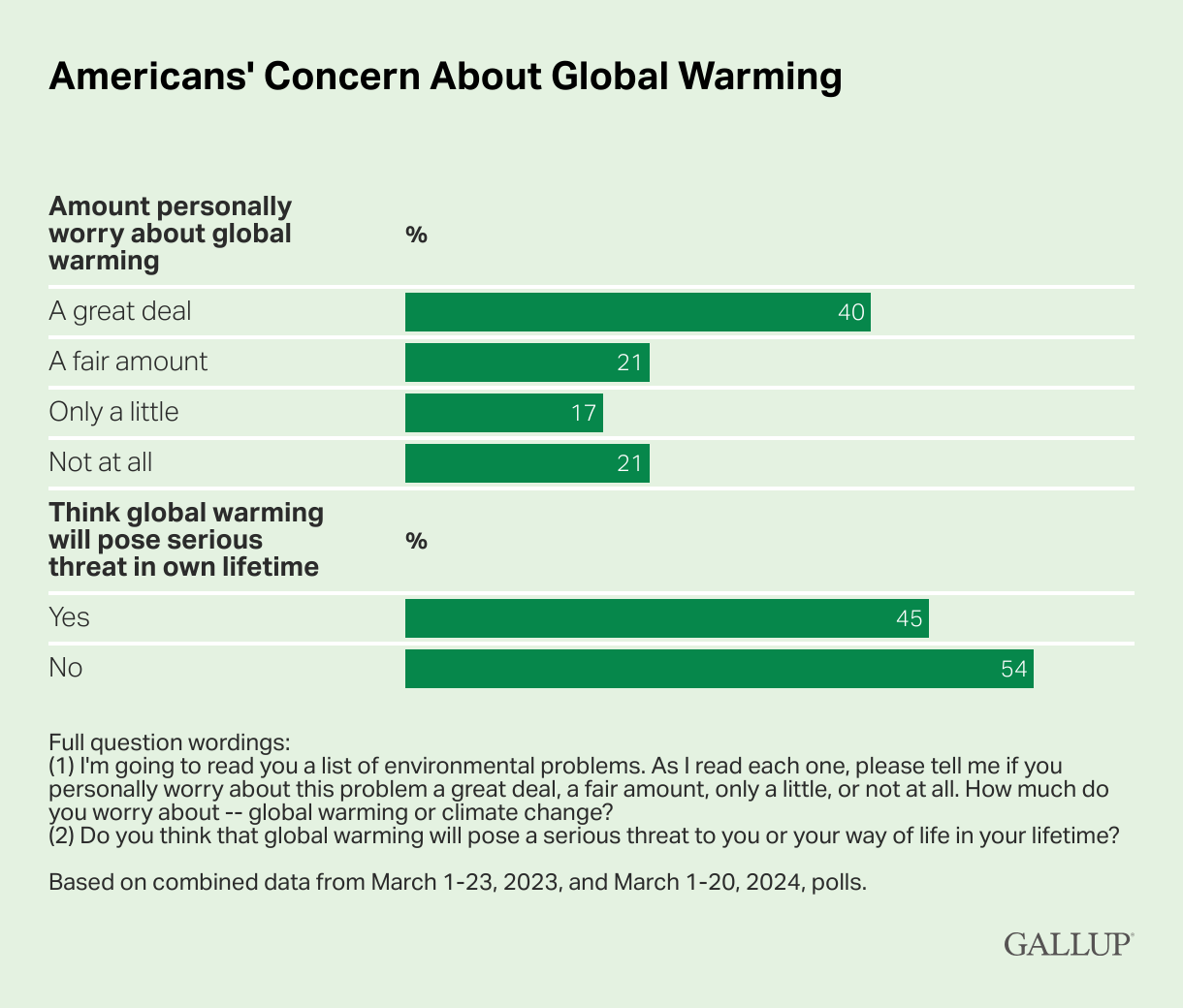

By 2030, climate change’s impact on high-temperature days will double, but only 61% of United States adults are concerned about global warming or climate change (Inc, 2024). Concern about climate change is not new either – it has received increasing media and partisan attention dating into the late 1980s (Dunlap & McCright, 2008; Inc, 2024; Treen et al., 2020). Since 2008, the number of high-temperature days have tripled which decreases overall wellbeing specifically in countries who have less GDP or growing economies (Gallup Inc., 2022). Risks extend into flooding, high temperature, agricultural issues, food insecurity, and the like (Gallup Inc., 2022). However, the most intense impacts of Climate Change are disproportionately in the Global South, thus allowing for its intense politicization in the United States. People who are not immediatley impacted may have less incentive to take actions which mitigate climate change, however, this is rapdily changing (Hao and Doyle, 2025).

Increased polarization has been identified for the past twenty five years in research, identifying that “Americans’ opinions on environmental issues has [had] increased association between an individual’s political identity and their opinions on the environment generally” (Dunlap & McCright, 2008; Coma et al, 2024). Shift in opinion coincides with a time where the United States is increasingly impacted by climate change. In 2024, the United States spent over twenty five billion dollars responding to climate related disasters (Hao and Doyle, 2025). Despite this increase, politcal polarization furthers a deep rooted climate divide. This polarization impacts the way climate policy is negotiated and viewed at both the regulation and interactional levels. Many scholars identify the most salient factor in one’s belief in climate change and its legitimacy is one’s partisian affiliation (Coma et al, 2024; Hao and Doyle, 2025).

Climate change has become an increasingly polarizing issue through partisan lines – and increasing in recent decades. Partisan views have developed into a social identity of sorts, thus many controversial topics have become amalgamated into believing the ‘Democrat’ or ‘Republican’ view of such debates (Dunlap et al., 2016). Historically environmental protections have received bi-partisan support, yet after the 2008 election, perceptions began to change (Dunlap et al., 2016). The Republican party demonstrates more within party variability for beliefs about climate change (Coma et al., 2024). The increase in access to mass media may contribute to increasing political polarization too. Liberal leaning news sources are more likely to report upon climate change action, while conservative news sources challenge this – a recent headline from Fox News illustrates this: “Dems blame LA fire on ‘climate change’ despite city cutting fire department budget” (Adame et al., 2025; Spady, 2025). Mass media specifically contributes a significant role in shaping partisan beliefs about climate change (Adame et al., 2025).

Donald Trump has become president, now for the second time, leading a Republican Trifecta, with control over the Huse, Senate, and Presidency. This positions him to make big changes to current climate change policy. The Republican party tends to away from policies which attempt to mitigate climate change and, in some cases, pass policy which specifically destructs the Democrat’s attempt to climate policy. An example of this is his recent policy to pull out of the Paris Climate Agreement, impacting the views of peer countries (such as China) to take action against climate change (Dunlap et al., 2016; Jones et al., 2025). Further expectations about Trump’s climate policy are roll backs for chemical regulations and other types of pollution citing the economy as his main motivation (Jones et al., 2025).

Donald Trump has become president, now for the second time, leading a Republican Trifecta, with control over the Huse, Senate, and Presidency. This positions him to make big changes to current climate change policy. The Republican party tends to away from policies which attempt to mitigate climate change and, in some cases, pass policy which specifically destructs the Democrat’s attempt to climate policy. An example of this is his recent policy to pull out of the Paris Climate Agreement, impacting the views of peer countries (such as China) to take action against climate change (Dunlap et al., 2016; Jones et al., 2025). Further expectations about Trump’s climate policy are roll backs for chemical regulations and other types of pollution citing the economy as his main motivation (Jones et al., 2025).

In contrast, Democrat’s favor more climate forward climate change policies. The party traditionally exhibits a sense of urgency to take climate mitigating actions (Hao and Doyle, 2024). This is evidenced in their recent political agenda. In 2022, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) was passed by the Senate, totaling over 300 billion dollars to invest in global warming (Yearwood, 2022). The IRA was the "largest investment in clean energy and climate action" in history (Hao and Doyle, 2025). This bill is claimed as “critical to humanity”, as climate change is viewed by many as something which impacts many people across the world (Yearwood, 2022). Furthermore, this bill supports clean energy, electric vehicle tax credits, and broader emission goals.

In contrast, Democrat’s favor more climate forward climate change policies. The party traditionally exhibits a sense of urgency to take climate mitigating actions (Hao and Doyle, 2024). This is evidenced in their recent political agenda. In 2022, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) was passed by the Senate, totaling over 300 billion dollars to invest in global warming (Yearwood, 2022). The IRA was the "largest investment in clean energy and climate action" in history (Hao and Doyle, 2025). This bill is claimed as “critical to humanity”, as climate change is viewed by many as something which impacts many people across the world (Yearwood, 2022). Furthermore, this bill supports clean energy, electric vehicle tax credits, and broader emission goals.

Donald Trump’s plans for office aim to directly disassemble the effort by the Democrats, claiming “to further defeat inflation, my plan will terminate the Green New Deal, which I call the Green New Scam… and [I will] rescind all unspent funds under the misnamed Inflation Reduction Act” (Martínez, 2024). Not only is the Republican Party anti-climate change, they actively block and dismantle what policy the Democrat Party passes – this is not new to the Trump Era either, during 2008 a ‘sturdy legislate wall’ was established against the Obama Administration (Dunlap et al., 2016). Are these partisan divides present in citizen behavior as well or do these generalizations result on pluralistic ignorance? Dixon et al says no – with four out of five climate change polices (tax credits for carbon capture, powerplant restrictions, solar panel and wind turbine farms) received fifty percent or more of public approval (Dixon et al., 2024). Dixon et al claim that the actualized views in response to climate change are less than what is expected. However, these findings are contested by Gallup polls, which demonstrate over half of Republican Voters believe that “the seriousness of global warming is generally exaggerated in the news” and only 41% of Republican voters believe the “effects of global warming have already begun” (Dunlap et al., 2016).

Gender may play a difference in how an indivudal may concieve both their political identity and position on climate change. Women are more likely to identify with the Democrat political affiliation, which may skew how gender and party affiliations are respenteted in climate change support (Coma et al., 2024). Similarly, the political cues a party enacts are percived differently along gender lines. Repulican men are more likely to assign meaning to symbolic imagery (like the flag of The United States) or to party functions (Coma et al., 2024). This echoes the differences identified by Stern and Dietz with increased concern by women about environmental degredation for others, weaker climate mitigation behaviors by mmen, and stronger biospheric alturistic cliamte attitudes held by women (Stern and Dietz, 1994). These differences may present themselves and compound along paritisan lines and gender differences in partisian composition.

Political sponsership and affiliation matters most for Republican men. When a climate bill is proposed by a bipartisan group of senators support by Republican men is about 23%, however, when proposed by a Democrat group support decreases to just above 5%. These differences are noticeable, but not significant in gender differences in the Democratic party, or even Republican women who do not illustrate a statistical difference between sponser preference (Coma et al., 2024). These findings suggest that for a more meaningful support from citizens, bipartisan groups making climate change bills are more effective. However, the clear polarization in even climate change beliefs suggests that this may be challenging.

Understanding in more depth the manifestations of such polarization may inform in what ways climate policy will develop, especially over the next four years, and who will be leading the change. Recent fear around the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) illustrate tangible concern rooted in polarization (Jones et al., 2025). Despite scientific evidence to the continuing changes in our climate, polarization reigns most impactful as “many politicians struggle to overcome their partisan divides, hindering a uniform and collective effort to endorse policies aimed at mitigating climate change” (Jud & Nguyen, 2024).

Polarization is what fuels my interest in better understanding the representations of climate change through news and policy. I outline two research questions, with five sub-considerations within each:

- How is climate change represented in climate policy passed as the federal level?

- What ways does news coverage reflect polarization in regards to climate change?

First, the question “how is climate change represented in climate policy passed at the federal level” aims to explore the way policy is used to institutionalize polarized debates. I would like to explore in more depth how different states pass laws with different topics of concern. Next, I will consider the overall sentiment of the documents. Third, I will generate a readability score for each document to see if climate forward policies or anti-environmental policies use more complicated language. Finally, I am interested in addressing potential overlaps in climate policy that are not bi-partisan supported bills to see if such polarization is more contested than represented.

Second, news coverage plays a large role in how people receive information, process it in accordance with their values system, and share it with their close social network. In my second question, “what ways does news coverage reflect polarization in regards to climate change?” I will consider how media either solidifies or challenges prior assumptions about climate change and its polarization. Second, I am interested in knowing more about how news channels cater to their audiences through headlines. This leads into my third point of interest when considering the similarities in language used between different news sources – so if there is a liberal leaning news source what is the overlap in language used (or differences) with a conservative news source. Finally, I am interested in tracking the different language used to express concern or disbelief in climate change to help illustrate multiple beliefs centering global warming.

Image Attributions: (1): Gallup Inc (2): (Saul Loeb / AFP / Getty) (3): PBS (4): NASA

Bibliography:

Adame, B. J., Corman, S. R., Endres, C. J., Farmer, R. D., & Awonuga, T. (2025). How partisan news outlets frame vested interests in climate change. Journal of Environmental Management, 375, 124159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2025.124159

Azdren Coma, Erik W. Johnson & Philip Schwadel (2024) Elite Cueing, Gender, and the Partisan Gap in Environmental Support, The Sociological Quarterly, 65:4, 448-468, DOI: 10.1080/00380253.2024.2347917

Dixon, G., Clarke, C., Jacquet, J., Evensen, D. T. N., & Hart, P. S. (2024). The complexity of pluralistic ignorance in Republican climate change policy support in the United States. Communications Earth & Environment, 5(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01240-x

Dunlap, R. E., & McCright, A. M. (2008). A Widening Gap: Republican and Democratic Views on Climate Change. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 50(5), 26–35. https://doi.org/10.3200/ENVT.50.5.26-35

Dunlap, R. E., McCright, A. M., & Yarosh, J. H. (2016). The Political Divide on Climate Change: Partisan Polarization Widens in the U.S. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 58(5), 4–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/00139157.2016.1208995

Gallup Inc. (2022). Climate Change and Wellbeing Around the World. Gallup.

Hao, Feng, and Joshua Doyle. “How Does Social Trust Shape the Politicization of America’s Climate Change Perception?—A Study of Two National Surveys in 2022 and 2023.” Sociology Compass 19, no. 2 (2025): e70035. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.70035.

Inc, G. (2024, December 13). Are Americans Concerned About Global Warming? Gallup.Com. https://news.gallup.com/poll/355427/americans-concerned-global-warming.aspx Jones, N., Witze, A., Tollefson, J., & Kozlov, M. (2025). What Trump 2.0 means for science: The likely winners and losers. Nature, 637(8046), 532–535. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-025-00052-z

Jud, S., & Nguyen, Q. (2024). Disasters and Divisions: How Partisanship Shapes Policymaker Responses to Climate Change (SSRN Scholarly Paper No. 4870935). Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4870935

Martínez, A. (2024, November 15). Trump wants to “Drill, baby, drill.” What does that mean for climate concerns? NPR. https://www.npr.org/2024/11/13/nx-s1-5181963/trump-promises-more-drilling-in-the-u-s-to-boost-fossil-fuel-production

Spady, A. (2025). Dems blame LA fire on “climate change” despite city cutting fire department budget ; Fox News. Fox News. https://www.foxnews.com/politics/dems-blame-fire-climate-change-despite-cutting-fire-department-budget

Stern, P. C., & Dietz, T. (1994). The Value Basis of Environmental Concern. Journal of Social Issues, 50(3), 65–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1994.tb02420.x

Treen, K. M. d’I., Williams, H. T. P., & O’Neill, S. J. (2020). Online misinformation about climate change. WIREs Climate Change, 11(5), e665. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.665

Yearwood, L. (Director). (2022, August 7). A look at the policies in the Democrats’ historic climate bill [Broadcast]. In PBS News. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/a-look-at-the-policies-in-the-democrats-historic-climate-bill